How to Use Python Pointers

Have you ever worked in programming languages like C++ or C?

If yes, you would have definitely come across the term pointers .

Every variable has a corresponding memory location and every memory location has a corresponding address defined for it. Pointers store the address of other variables.

Surprisingly, pointers don’t really exist in Python. If that is the case, what am I writing about here?

Everything is an object in Python. In this article, we will look at the object model of Python and see how we can fake pointers in Python.

You can skip to any specific section of this Python pointers tutorial using the table of contents below.

Why Don’t Pointers Exist in Python?

Nobody knows why pointers don’t exist in Python.

Even in basic programming languages like C and C++, pointers are considered complex.

This complexity is against the Zen of Python and this could be the reason why Python doesn’t speak about why it doesn’t include pointers.

Said differently, the objective of Python is to keep things simple. Pointers aren’t considered simple.

Though the concept of pointers is alien to Python, the same objective can be met with the help of objects. Before we discuss further on this, let us first understand the role of objects in Python.

Everything is an object in Python.

If you are just getting started with Python, use any REPL and explore the isinstance() method to understand this.

More specifically, the following code proves that the int , str , list , and bool data types are each objects in Python.

print(isinstance(int, object)) print(isinstance(str, object)) print(isinstance(list, object)) print(isinstance(bool, object))This proves that everything in Python is an object.

A Python object comprises of three parts:

Reference count is the number of variables that refer to a particular memory location.

Type refers to the object type. Examples of Python types include int , float , string , and boolean .

Value is the actual value of the object that is stored in the memory.

Objects in Python are of two types – Immutable and Mutable.

It is important to understand the difference between immutable and mutable objects to implement pointer behavior in Python.

Let’s first segregate the data types in Python into immutable and mutable objects.

| Immutable | Mutable |

|---|---|

| int | list |

| float | set |

| str | dict |

| bool | |

| complex | |

| tuple | |

| Frozenset |

Immutable objects cannot be changed post creation. In the above table, you can see that data types that are commonly used in Python are all immutable objects. Let’s look at the below example.

When you run this script in your REPL environment, you will get the memory address of value.

Now, let’s modify the value of x and see what happens. The value of x in the memory 94562650443584 is 34 and that cannot be changed. If we alter the value of x, it will create a new object.

x = 34 y = id(x) print(y) x += 1 y= id(x) print(y)Use the is() to verify if two objects share the same memory address. Let’s look at an example.

If the output is true, it indicates that x and y share the same memory address.

Mutable objects can be edited even after creation. Unlike in immutable objects, no new object is created when a mutable object is modified. Let’s use the list object that is a mutable object.

numbs = [1, 1, 2, 3, 5] print("---------Before Modification------------") print(id(numbs)) print() ## element modification numbs[0] += 1 print("-----------After Element Modification-------------") print(id(numbs)) print()---------Before Modification------------ 140469873815424-----------After Element Modification------------- 140469873815424Note that the address of the object remains the same even after performing an operation on the list.

This happens because list is a mutable object. The same concept applies to other mutable objects like dict or set mentioned in the table presented earlier in this tutorial.

Now that we have understood the difference between mutable and immutable objects, let us look at Python’s object model.

Variables in C vs Variables in Python

Variables in Python are very different from those in C or C++.

More specifically, Python doesn’t have variables. They are called names instead. To understand how variables in Python differ from that in fundamental programming languages like C and C++, let’s look at an example.

First, let’s define a variable in C.

What does the above code actually do?

- Allocates a memory for the defined data type, which in this case is int

- Allocates a value 10 to the memory location, say 0x5f3

- Indicates that the variable v takes the value 10

In C, if you want to change the value of v at a later point, you can do this.

Now, the value 20 is allocated to the memory location 0x5f3 . Since the variable v is a mutable object, the location of the variable did not change though the value of it changed. That is, the v defined here is not just the name of the variable but also its memory location.

Now, let’s assign the value of v to a new variable.

A new variable new is now created with the value 20 but this variable will have its own memory location and will not take the memory location of the variable whose value it copied.

In Python, names work in a contrasting way than what we just saw.

Let’s rewrite the Python equivalent of the above code to see this principle in action.

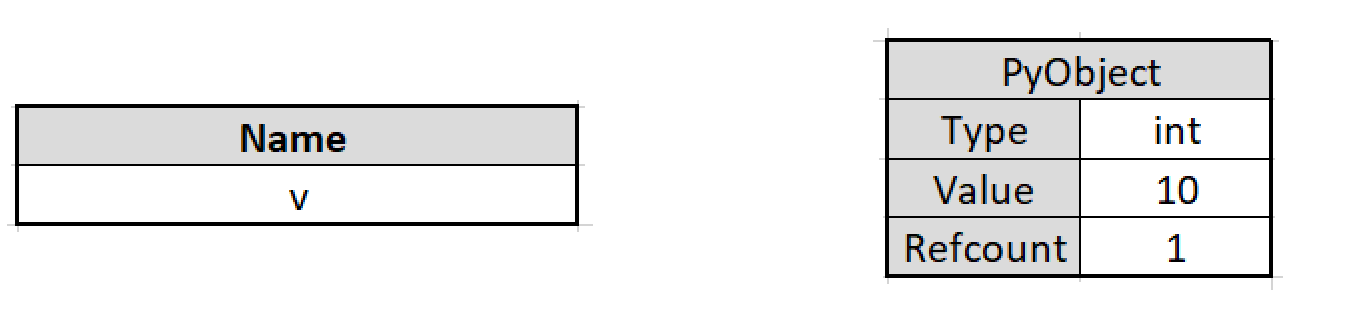

- Creates a new Python object

- Sets the data type for the Python object as integer

- Assigns a value 10 to the PyObject

- Creates a name v

- Points v to the newly created PyObject

- Increases the refcount of the newly created Python object by 1

Let’s visualize and make our understanding simple.

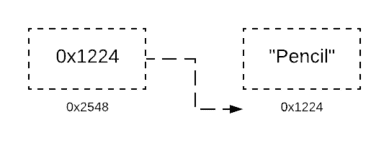

Unlike in C, a new object is created and that objects owns the memory location of the variable.

The name defined v , does now own any memory location.

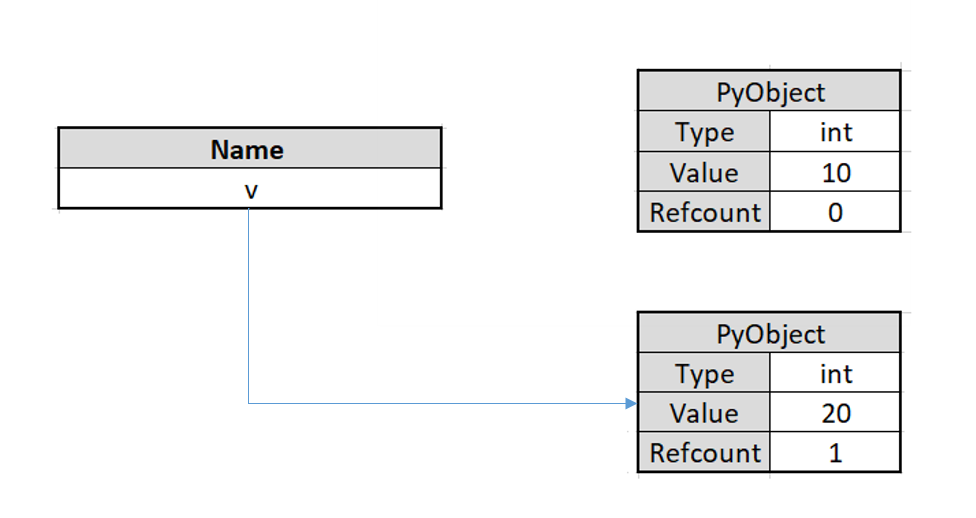

Now let’s assign a different value to v .

Let’s see what happens here:

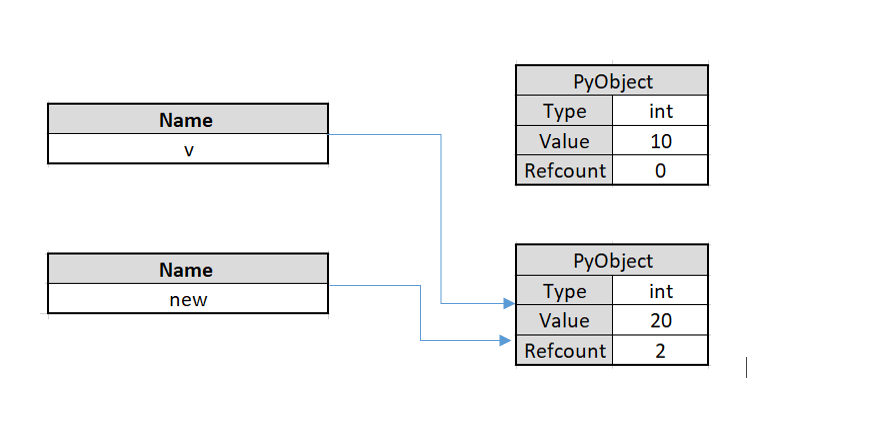

- First this creates a new PyObject

- Sets the data type for the PyObject as integer

- Assigns a value 20 to the PyObject

- Points v to the newly created PyObject

- Increases the refcount of the newly created PyObject by 1

- Decreases the refcount of the already existing PyObject by 1

The variable name v now points to the newly created object. The first object which had a value 10 now has a refcount equal to zero. This will be cleaned by the garbage collector.

Let’s now assign the value of v to a new variable.

In Python, this creates a new name and not a new object.

You can validate this by using the below script.

The output will be true. Note that new is still an immutable object. You can perform any operation on new and it will create a new object.

Pointer Behavior in Python

Now that we have a fair understanding of what mutable objects are let us see how we can use this object behavior to simulate pointers in Python. We will also discuss how we can use custom Python objects.

We can treat mutable objects like pointers. Let’s see how to replicate the below C code in Python.

#include void add(int *a) < *a += 10; >void main() < int v = 10; printf("%d\n", v); add(&v); // to extract the address of the variable printf("%d\n", v); >In the above code, v is assigned with a value 10 . The current value is printed and then the value of v is increased by 10 before printing the new value. The output of this code would be:

Let’s duplicate this behavior in Python using a mutable object. We will use a list and modify the first element of the list.

def add(v): v[0] += 1 new = [10] add(v) v[0]Here, add() increments the first elements value by one. So, does this mean pointers are present in Python? No! This was possible because we used a mutable type, list. Try the same code using tuple. You will get an error.

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 1, in File "", line 2, in add_one TypeError: 'tuple' object does not support item assignmentThis is because tuple is an immutable type. Try using other mutable objects to get similar desired output. It is important to understand that we are only faking pointer behavior using mutable objects.

We can create real pointers in Python using the built in ctype modules. To start, store your functions that use pointers in a .c file and compile it.

Write the below function into your .c file.

Assume our file name is pointers.c . Run the below commands.

$ gcc -c -Wall -Werror -fpic pointers.c $ gcc -shared -o libpointers.so pointers.oIn the first command, pointers.c is compiled to an object pointers.o . Then, this object file is taken to produce *libpointers.so to work with ctypes .

import ctypes ## libpointers.so must be present in the same directory as this program lib = ctypes.CDLL("./libpointers.so") lib.pointersctypes.CDLL returns the shared object libpointers.so . Let us define add() function in the libinc.so shared object. We have to use ctypes to pass a pointer to the functions defined in a shared object.

add = lib.pointers ## define argtypes add.argtypes = [ctypes.POINTER(ctypes.c\_add)]We will get an error if we try calling this function using a different type.

Traceback (most recent call last): File "", line 1, in ctypes.ArgumentError: argument 1: : expected LP_c_int instance instead of inThe error states that a pointer is required by the function. You must use a C variable in ctypes to pass the variable reference.

v = ctypes.c_add(10) add(ctypes.byref(v)) vHere v is the C variable and byref passes the variable reference.

As we saw in this tutorial, pointer behavior can be implemented in Python though they are technically not available in the Python language.

While we used mutable objects to simulate pointer behavior, the ctype pointers are real pointers.

If you enjoyed this article, be sure to join my Developer Monthly newsletter, where I send out the latest news from the world of Python and JavaScript:

Pointers in Python (Explained with Examples)

Summary: In this tutorial, we will learn what are pointers in Python, how they work and do they even exist in Python? You’ll gain a better understanding of variables and pointers in this article.

What are the Pointers?

Pointers in the context of high-level languages like C++ or Java are nothing but variables that stores the memory address of other variables or objects.

We can reference another variable stored in a different memory location using a pointer in high-level programming languages.

Unlike variables, pointers deal with address rather than values.

Does Python have Pointers?

Sadly, Python doesn’t have pointers like other languages for explicit use but is implemented under the hood.

Types such as list, dictionary, class, and objects, etc in Python behave like pointers under the hood.

The assignment operator = in Python automatically creates and assigns a pointer to the variable.

The above statement creates a list object and points a pointer to it called “l”.

If you assign the same list object both to two different variables m and l, they will point to the same memory location.

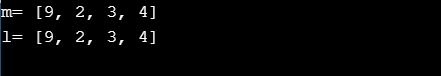

#Assign l = [1,2,3,4] m = l #Modify only m m[0] = 9 #changes reflected by both m and l print("m =", m) print("l =", l)To make sure that m and l are pointing to same object lets use is operator.

>>> l = [1,2,3,4] >>> m = l >>> print(m is l) TruePython “is” operator works differently from “==” operator. “==” operator in Python returns compares the content of the object whereas the is operator compares the object’s reference.

Also, it is important to note that python deletes an object only when all the pointers to the object is deleted.

Use del m or del l will only delete the variable not the underlying object to which it was referencing.

Python will still keep the object in the memory until all the pointers pointing to the list object are deleted.

Are numbers and strings also Pointers?

The answer is NO. Simples types such as int , str , float , bool , etc do not behave like a pointer.

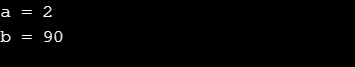

Consider the following python snippet:

#Declare variables a = 9 b = a #modifying a a = 2 print("a =",a) print("b =",b)As we can see, changing the value of “a” doesn’t change “b”. Hence unlike a list, the value of integer variables a and b are stored in different memory addresses or locations.

On a final note, we conclude that Python doesn’t have pointers but the behavior of pointers is implemented under the hood by the python for a few types and objects.